The Hidden Reason Studios Keep Saying “No AI”

The real fight over AI in Hollywood isn’t about talent. It’s about control.

TLDR:

The real fight over AI in Hollywood isn’t about talent. It’s about control. Even art answers to a framework where creativity is graded.

Awards shows and studios remind us that art doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It lives inside systems: eligibility rules, contracts, distribution frameworks, and legal definitions that decide what counts and what doesn’t. Heated Rivalry is a clear example. Despite popularity and critical praise, it wasn’t eligible for the Primetime Emmys because it was fully produced in Canada and only later acquired by U.S. platforms. The issue wasn’t quality. It was structure.

That same logic now shapes how AI is discussed in film.

In moments of sale or merger, the mechanics of how a studio creates its work suddenly aren’t just artistic details. They become part of how lawyers, investors, and insurers assess risk and value. When Warner Bros. emphasized its “traditional production pipeline,” it wasn’t just describing a creative process. It was signaling stability at a time of restructuring, investor scrutiny, and high-stakes valuation amid ongoing acquisition interest.

In this context, “traditional pipeline” points to:

Human-led creation

Writers, directors, actors, crews, editors, VFX, sound.Established legal frameworks

Clear authorship, chain of title, union contracts, insurance.Limited AI uncertainty

Fewer unresolved questions around copyright, training data, liability, and residuals.

That’s why it was notable when James Gunn clarified that Krypto in Superman (2025) was created with CGI, not generative AI, and that the DCU would not be using AI in its animation pipeline. He didn’t have to make that distinction, but doing so placed the project firmly within established, human-led production methods at a time when how something is made is almost as closely scrutinized as what is made.

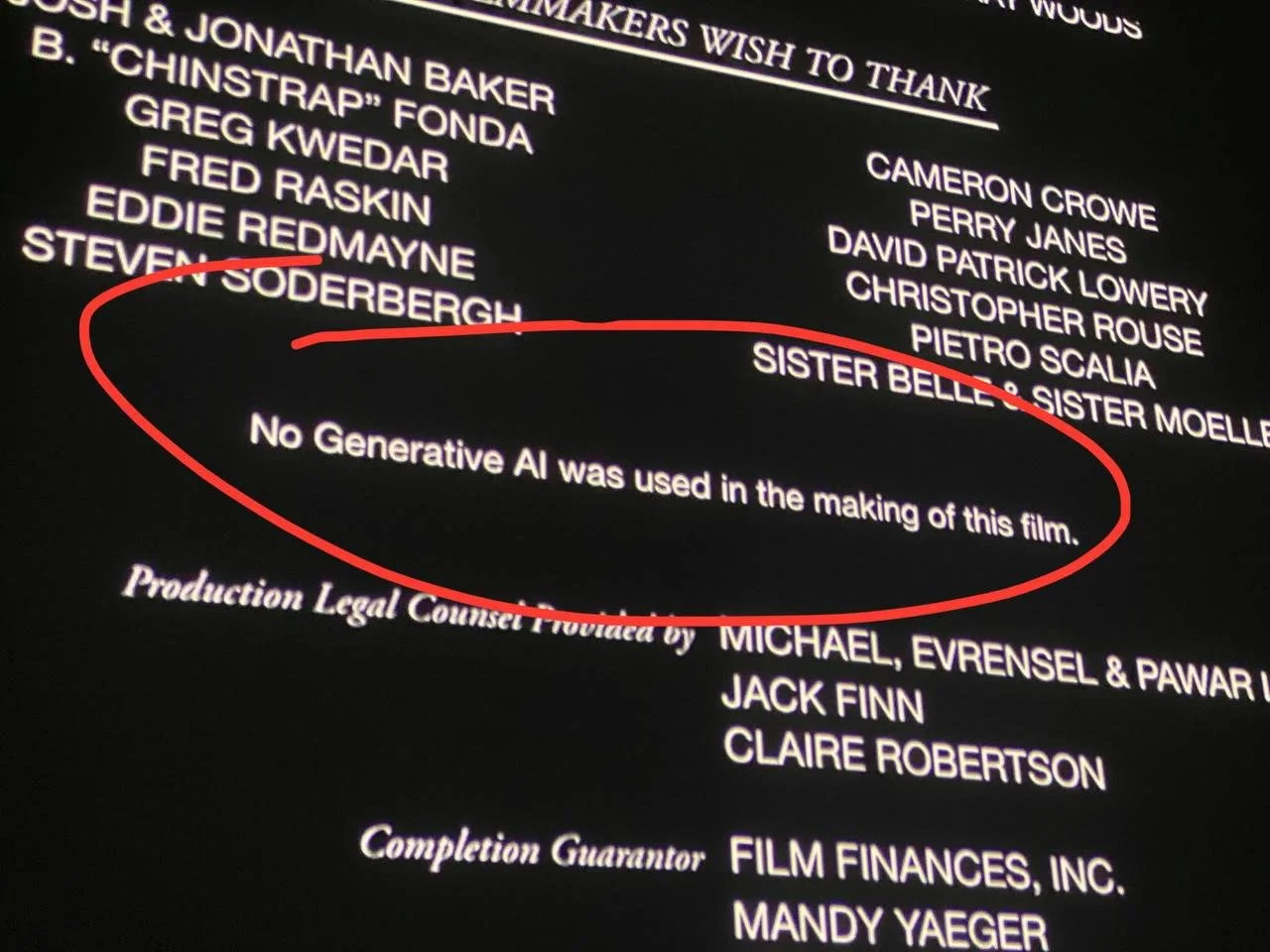

The same dynamic appears in Heretic’s “no AI used” credit. It wasn’t legally required. It may read like it’s for the audience, but it’s likely just as much for the people behind the scenes, including but not limited to insurers, distributors, investors, and award bodies. In that light, those disclaimers start to look less like moral statements and more like strategic reassurance to the decision-makers who determine what gets protected, financed, and recognized. All of whom care about:

Clean ownership

Clear liability

Enforceable labor agreements

Auditable production history

Not every major creative project has taken a hard line against AI — and in some cases, the industry is actively grappling with how to integrate it. For example, in the 2025 awards season there were reports that films like The Brutalist used AI tools to assist aspects of post-production, such as refining Hungarian dialogue pronunciation and architectural imagery during editing. This sparked public backlash and debate over whether AI’s involvement should affect recognition and awards prospects.

And on the awards side, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences updated its rules to explicitly acknowledge generative AI, noting that AI use doesn’t automatically hurt a film’s eligibility but that how it’s used, and the degree of human creative authorship involved, does matter.

These examples complicate the idea that the industry uniformly rejects AI. In practice, studios and creators are negotiating where AI fits: often using it quietly in technical roles, sometimes challenging it legally, and sometimes publicly distancing themselves from it as a creative tool. What’s clear is that the conversation isn’t just about whether AI exists or works, but about who gets to decide how it’s used, and under what terms.

But beyond contracts, audits, and liability, there’s a question that doesn’t disappear just because it’s uncomfortable.

On a moral level, I don’t think the central question should be avoided: Is generative AI art?

What often gets lost in the noise is that AI-assisted creation is rarely just a single prompt and a finished result. Like Photoshop, collage, or mixed media, it involves selection, iteration, revision, and human judgment. A tool produces options, but a person decides what stays, what changes, what fails, and what finally represents the idea in their head. The intention remains human, even if the execution is assisted.

We already accept this in other fields. A designer who uses Photoshop’s generative fill is still the artist. A filmmaker who relies on CGI is still the director. A founder who builds a website using a UI builder rather than hand-coding every line is still the creator of the product. We don’t say the website “wasn’t really made” because the person didn’t write raw HTML. We judge authorship by decision-making, not by tool purity.

So the discomfort isn’t really about whether something was generated. It’s about whether authorship feels diluted. But if a human guides the process, curates the output, reshapes it, and takes responsibility for the final form, is that fundamentally different from any other assisted creative workflow?

This is where the debate becomes less about technology and more about how we define creation itself.

So when studios emphasize “traditional pipelines” or projects label themselves “no AI,” it isn’t really about rejecting the technology. The conversation may look like it’s about tools, but behind the fog, it’s about something else entirely: fitting work inside systems that know how to value it, regulate it, insure it, and defend it.